The Allure of the Rolex Daytona

I first developed an interest in the Rolex Daytona long before I knew it was “important”.

My dad’s always been a Rolex guy. He wore a 34mm Oyster Perpetual for almost thirty years before he brought it in for its first service sometime in the early nineties. When he came back – watch keeping good time again and looking like new, pockets full of free chocolate from the service centre’s reception area – he brought that year’s catalogue with him. Page after page of life-sized photos of the Rolex lineup of the time.

My dad’s always been a Rolex guy. He wore a 34mm Oyster Perpetual for almost thirty years before he brought it in for its first service sometime in the early nineties. When he came back – watch keeping good time again and looking like new, pockets full of free chocolate from the service centre’s reception area – he brought that year’s catalogue with him. Page after page of life-sized photos of the Rolex lineup of the time.

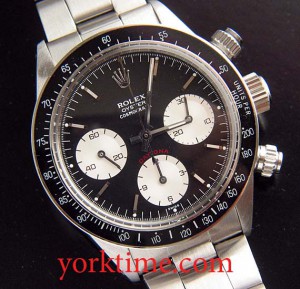

Since I was a kid, I’d always liked shiny, complicated things: planes, cars, hi-fi equipment, computers. Flipping through that brochure, the Daytona was, diamond-festooned jewelry pieces aside, the shiniest, most complicated Rolex in the book. And, therefore, the best. There wasn’t a lot of text in the brochure that I can remember – just some very basic specs about size, material, movement, all set in the Univers type that Rolex favoured at the time – so I spent a lot of time staring at the pictures. And, after a few hours, I decided that the best Daytona was actually the steel version. Shiny, yes, but functional and sporty-looking and full of stuff to play with: pushers that needed to be unscrewed, screw-down Oyster crown, chronograph. So much writing on the dial, too! I think I was fourteen at the time.

My love of shiny, complex watches kind of waned through high school and university; in addition to not having the financial means to afford them, there were plenty of other distractions at the time. But always in the back of my mind was the Daytona. And when the watch bug bit me midway through my twenties, when I could finally afford something nice to strap to my wrist, the thought was always there: one day.

Around that time, friend of mine had introduced me to a couple of Web sites for watch geeks, and I was spending too much of my free time trawling for information on them. Turned out that I wasn’t the only one vaguely obsessed by the Daytona – the steel version in particular. Turns out that, despite being the cheapest of all the Daytona models (at the time, a new one would run just over $4,000), a steel version was a lot harder to get than the ubiquitous $25,000 gold version. Tentative visits to a few watch stores confirmed that: none of them had a steel Daytona to see or try on and none of them took me all that seriously when I asked if it would be possible to order one.

Which just about confirmed what I’d read online: whether it’s Rolex itself, or the dealers, supply of steel Daytonas is artificially limited – you’ll have a tough time buying one new unless you’ve got a good relationship with your jeweler. Finding one on the used market was certainly possible, but you’d likely be paying more than you’d pay for a new one. So in addition to being the shiniest, most complicated and best Rolex, the Daytona also seemed to be a rock-solid investment.

So what is it about the Daytona that makes it such a sought-after thing, beside just looking cool?

If you’re into cars and racing at all – and I always have been – it turns out that the Daytona is a big deal to racers and fans. Rolex has been sponsoring the 24 Hours of Le Mans and the 24 Hours of Daytona forever. Winning drivers of the Daytona race get a steel (not a gold; that would be expensive!) Daytona with a special engraving on the back.

Want to know how talented, fast, consistent and reliable an endurance driver is? Find out how many steel Daytonas he has in his collection. I got to go to Porsche’s annual motorsport awards dinner recently; I’d never seen so many Daytonas in one room. The MC was even making fun of one of the night’s honourees because he only had ONE of them, when so many of the other guys on stage had three, four, five, even more. Suddenly, I was feeling a little self-conscious; my retail-purchased, un-engraved, un-earned 116250 didn’t feel quite so special anymore.

You’ve probably heard of the “Paul Newman” Daytona – a reference to a design that was a commercial flop back in the sixties, with contrasting subdials that featured larger, bolder numbers. There’s a lot of conflicting information about the connection to Newman out there; some say he wore one in the movie “Winning,” but you never see one on-screen. Others claim that his wife, Joanne Woodward, gave him one as a present before he started shooting the film, with an engraving telling him to be safe. Whatever the case, Newman Daytonas are rare, pricey, and crazily sought-after – the perfect match to your vintage European sports car and likely to be almost as expensive.

Like many watch-collecting trends, the obsession with Daytonas seems to have started with Italy, where style-conscious (and one imagines, car-loving) gents loved its combination of a classically-styled case, rugged functionality and some complicated functions to play with. Whether you’re talking about a modern 40 mm version on the brushed-and-polished steel bracelet, or an earlier 37 mm model with polished steel bezel, a Daytona’s big enough to be sporty and legible, but thin enough and elegant enough to tuck under the cuff of your dress shirt. It’s a terrifically versatile piece. A Daytona’s presence makes your $50 jeans and $20 T-shirt look like a million bucks and reminds people that you may be wearing a $2,500 suit, but where you really belong is at the racetrack, not the boardroom.

If you are a racing driver, you’re unlikely to be timing your laps these days using a mechanical chronograph, especially one with screw-down pushers and, at least on contemporary Daytonas, nearly-illegible sub-dials. For those of us that aren’t, the presence of a Daytona on our wrist is a tangible link to a world where speed, performance, endurance, accuracy and precision mean a lot. It’s also probably a reminder to ourselves of the kind of guy we’d like to be.